Art without Edge

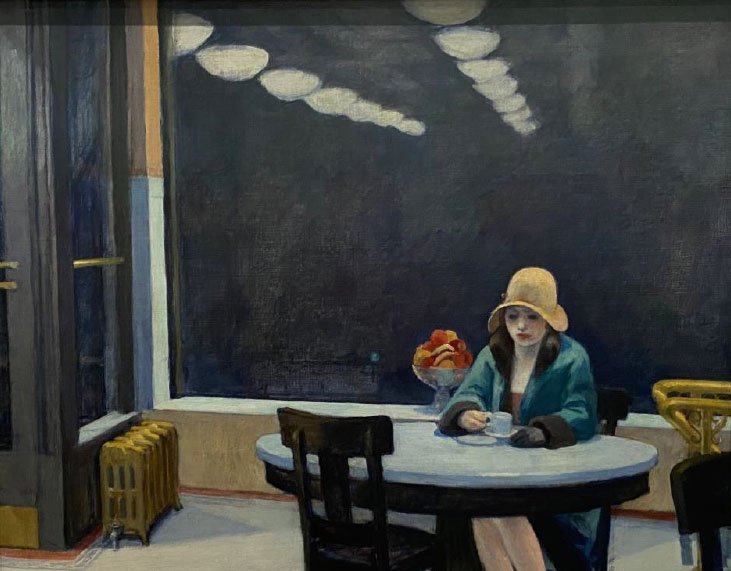

Edward Hopper, 1927, Automat, Oil on canvas, 28 × 36” (71.4 cm × 91.4 cm)

Hopper’s New York Exhibition, Whitney Museum of American Art, 2022

from Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa

Art with edge is the beautiful whim or grim, a Mona Lisa smile, a urinal by R, Mutt, Anselm Kiefer’s Exodus, and an Edward Hopper, who catches the grit of New York City in a painting of an overpass to a railway line or a woman alone in an automat. It is confrontation with the inexplicable, and a sense of being thrown into a reality never seen, or always seen but never appreciated. It is an energy expressed and a thought condensed, or never felt. Edge is hard to attain and difficult to keep. Like anything sharp, it dulls with repetition. In the '50s New York, art had edge.

The modernist edge was brought from Europe by artists: Duchamp, escaping WWI, Ernst, and Mondrian, escaping WWII. After the First World War, Americans: Pollock, Rothko, Guston, Gottlieb, Motherwell, Frankenthaler, and the immigrant Dutchman de Kooning jabbed the art world in the eye with Abstract Expressionism. In the ‘60s, Pop Art, led by Warhol, Oldenburg, Thiebaud, and Lichtenstein jolted the art world with their punches to the gut with soup cans, Mao mascara, soft cones, tasty pie slices, and comic book screams. But as the decades passed the shakes to the fine art establishment diminished. Perhaps this is because, as Duchamp implied without directly stating it, that the cultural establishment and in particular capitalists saw that there was value in art to be a commodity that renews itself with frequent eruptions. Minor quakes did happen, but they became less frequent and harder to identify. By the 2020s the American art capital, New York City, had lost its art edge. That is what I think.

I have been coming to New York City since I was a college student in the 1960s. The Museum of Modern Art had already enshrined Pollock and Rothko. The Whitney was in hot pursuit. The avant-garde galleries had found a new edge in hard-edge abstraction by the likes of Al Held and Knox Martin. At the Yale Summer Art School, I was lucky enough to join art students from across the country and be taught by Knox Martin, who demonstrated his hard edge by placing his pet tarantula in my palm and daring me to pet its spikey fur while the spider explored my nervous hand with its feet.

My first jab at being a painter was an homage to Jackson Pollack when I flicked brushes loaded with black and lavender house paint at a canvas to make cascades of colored rivulets. I liked doing freeform abstraction, but I quickly ran out of ideas. I moved on to laying masking tape all over canvases to define countless hard edges. This interest didn’t last long either, and I move on to abandoning the tape and then attempting to make color fields like I had seen in New York from Morris Lewis and Kenneth Nolan. Hard Edge Abstraction and Color Fields were not the sharp edge for long. Very quickly the edge was replaced by Pop Art, a conception of art that was a swipe at the intellectualism and seriousness of paint spatterers and rubbers of colored rectangles and cubes. Warhol and Oldenburg were the stars. I had moved on to thinking I could make narrow lines across the flat plane. Progress in world of edginess seemed to require the making of larger and larger canvases. My endeavors at six feet long and four feet high were miniscule compared to those of the really big painters. I drifted away from New York physically, but mentally my heart was still in the art world. I kept coming back to the city to prowl its Soho and Chelsea galleries.

In the fall of 2022, I visited New York City and spent most of that time visiting galleries in Chelsea and Brooklyn and museums in Manhattan, where I saw the Hopper exhibition, which captured a not pretty and not homey metropolis. Hopper nonetheless created a beauty that sharpens the eye to multifarious greys and the shadowy reality of the city. New York isn’t the gay Paris of Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s “Le Moulin de la Galette.” It’s a tough town. My conclusion that art in the private galleries in Manhattan had lost its edge was confirmed when my daughter, visiting from London, and I discussed this issue as one can only do in New York City with its typical frenetic pace on 8th avenue between 33rd and 34th Streets in front of Moynihan Hall, the new entry to Pennsylvania Station. We stood on the sidewalk with crowds shouldering their way into the station on our left and with traffic cones to our right marking a zone where bicyclists, motorcyclists, and electrified mopeds wove in and out around the cones and taxis poured down the constricted street clanking the iron plates covering ongoing excavations. The din backdropped a stimulating New York conversation. My daughter responded to my no edge conclusion that the problem with the art world was that it had gone completely corporate. I said that her attribution of corporate culpability was hardly news. She laughed and added that when there were no more edge movements, the result was an ideas and stylesfree for all for which the only marker for worth was the market. I agreed but added to my conclusion that there was a striving for edginess in all that I had seen in the galleries on only one street in Chelsea, 25th Street, where I had visited five galleries in the morning. Real edginess, I stated, had gone to Brooklyn.

Horse Sculpture. By Deborah Butterfield, Marlboro Gallery, NYC

I averred that the work I saw at the Henoch, Cheim and Read, Agora, Marlboro, and Pace Galleries was very professional. All the artists represented by these galleries were accomplished in how they handled paint, bent wire, finished PVC, or cast bronze, but there was no thing that made me see art from a different perspective or moved me emotionally. I remarked that I felt the situation to be curious because three of these galleries represented artists for whom I had a much respect. Cheim and Read represented Diane Arbus, Robert Mapplethorpe, Louise Bourgeois, and Al Held, but the painter Marco Pariani, whose work was on display in an exhibit titled “Trees and Traditions,” was repeating himself again and again in a vaguely abstract parody of Christmas trees and ornaments. He used a gimmick of stamping the perimeter of his canvases with a light stencil looking like Victorian wallpaper. I didn’t think this work had edge at all. Marlboro Gallery, which represents Magdalena Abakanowicz and Red Grooms, had an exhibit of simulated driftwood horse sculptures cast in bronze by Deborah Butterfield. I had previously seen her work in several museums in California. It is attractive, represents a clever idea, and would be impressive on the lawn of a billionaire’s mansion, but I couldn’t call it edgy. My daughter said I was jaded.

Richard Pousette-Dart, Oil Painting, Pace Gallery, NYC

Pace Gallery represents Chuck Close and Lynda Benglis. They were showing the work of Richard Pousette-Dart. I had seen his work in the 1960s. I don’t recall what I saw then as being as thickly layered as the work in this exhibition. He died in 1992. I thought perhaps he was an example of what becomes of an artist who plays the same card again and again. The edge became dull the more the artist piled up his paint in gooey layers. The edginess was still vaguely there, but it had transformed to a financial gain on an art bond. My daughter and wife smiled at my comparison. My daughter said my criticism was a bit strained. My wife asked me to tell what I really liked from our morning explorations. I shouted above blare of traffic that I liked the work of Janet Rickus we saw in the Henoch Gallery. I found her small paintings of pottery, fruit, and vegetables well done. They were as lovely as the 16th century Flemish still life paintings like Peter Claesz’s, but not as rigorous as Morandi’s subtle colors. The one I liked best was an oil painting called “Watermelon and Zucchini.” It had no price tag, so I asked its price. It was $25,000. It had no edge but was tasteful couch art for millionaires. I might not have the cash, yet I had a good eye for the most expensive stuff.

Janet Rickus, Watermelon and Zucchini, Oil on Canvas 14” x24” (35.56 x 60.96 cm)

Brooklyn was the place to go to see where edge had gone. I recounted to my daughter our trip crossing the East River on the Brooklyn Ferry, where you feel the swell of the ocean, see the Statue of Liberty in a twilight glow, land at Red Hook, and trudge along a high fence surrounding parking lots that once must have housed wharf structures, to the Pioneer Works non-profit organization occupying an old iron work foundry. In this mammoth space, we saw a huge video display called “The Mathematics of Consciousness” by Charles Atlas. On a long high wall of two banks of multiple blanked-out windows, the tapes appeared and disappeared with images -- sometimes of people, sometimes partial faces, or digital geometries while the whole wall between windows, the brick sills, transoms, and piers played a different video sequence of numbers and swirls. It was set-up that used the architecture of the space (in this example, the two story wall of windows) as an integral part of the video. It was an engaging melding of technology and art. It had me enthralled. The installation wasn’t an immersive experience like the museum shows in which the floors, walls, and ceilings totally plunge the visitor into the work of Vincent van Gogh (for example). These experiences are little more than Disneyland attractions that destroy the presence and the edge that the artist’s actual work was meant to be experienced up close, and in a small scale. I am sure that soon we will have a total plunge into a Jackson Pollock work supported by the Sherwin Williams Paint Corporation. This exhibit was different -- you could bring your brain with you and use your aesthetic sense to become engaged with a time-based video that was geometric, mathematical, and laden with dance. The images shifted and rearranged from blanked window to window and windows to wall. It was composition and vision as I had never seen them before. I felt I was at the edge of something new. It was sharp and demanded one’s attention. The work was change and it implied change. And edge as I see it is change.

One can experience change of art and in art in many ways at Pioneer Works. The venue is more than a non-profit gallery. Pioneer Works also has a smaller gallery for local artists. Anya Kielar showed several shadow boxes surrounded by fabric-covered walls. The shadow boxes are compositions of the same fabric of the wall, wrapped around foam to create multiple layers of figurative planes. There is a series of studio workspaces for artists and art technologists to work. It is embodiment of creativity. There is sure to be a lot of work with edge spilling from this place. Happy that I had seen the edge I was seeking, we recrossed two borders of New York City on the rolling ferry ride to experience edginess that remains in “the city that never sleeps” on 8th Avenue.

Charles Atlas, The Mathematics of Consciousness, Time-Based Video Installation, Pioneer Works, Brooklyn New York

Charles Atlas, The Mathematics of Consciousness, Time-Based Video Installation, Pioneer Works, Brooklyn New York

DISCLAIMER The views expressed on this website and blog are the opinions and conjectures of Carlton Davis and are not intended to malign, defame, or disparage any religion, ethnic group, race, group, organization, company, or individuals including artists, architects, authors, museums, cultural institutions, or galleries. The responsibility for all content on this website is my own and represent no other organizations or companies. Images shown on this website, in manuscripts, and blogs are my own unless fully attributed to the museum, artist or artist’s foundations or heirs. Carlton Davis is not responsible nor will be held liable or what anyone says, or comments about the blogs, articles, and manuscripts accessible from this site by responding to items permitted on this website. The accuracy of the information displayed on this site is correct as far as Carlton Davis knew at the time of provision of the information. Persons or organization linking to this site are responsible for the content of their link. Carlton Davis will not be responsible for the information on a link or any damages caused by the link. If material downloaded from the website causes damage or harm to the downloading site, Carlton Davis shall not be held libel.